At 92, Charles Aznavour Is Still With His First Love — His Audience

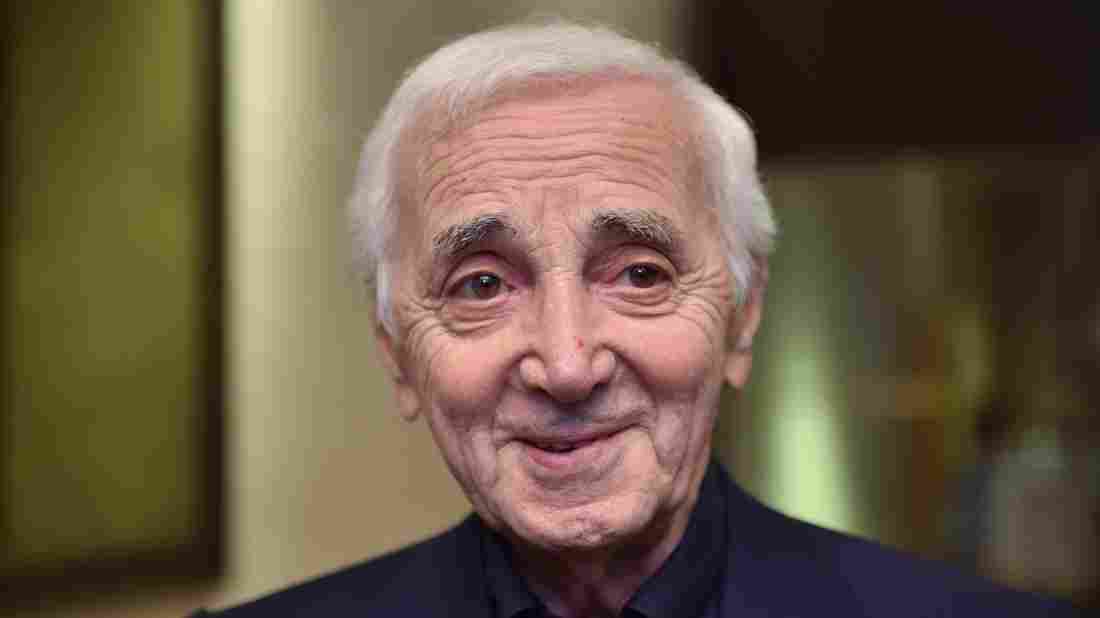

“Writing without performing is not interesting,” Charles Aznavour says. His U.S. tour ends in Hollywood this week. Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images

When I tell people that I recently talked to Charles Aznavour, I tend to get two questions. First, from people of a certain age, those who remember where they were when JFK was shot: “Charles Aznavour is still performing?” Second, from younger people, a more basic question: “Charles who?”

To answer the second question, Charles Aznavour is a French-born singer-songwriter who has written hundreds of songs, like “Yesterday When I Was Young,” which became a big hit in English back in 1969 when Roy Clark recorded his version of the tune. He was discovered by the great French singer Édith Piaf in 1946. He was also in the movies — he starred in François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player.

Now, to answer the first question: Yes, Charles Aznavour is still writing songs at age 92, and he is still performing. In fact, he’s touring the U.S. right now, because, as he tells me, “Writing without performing is not interesting.”

We met in a midtown Manhattan hotel. He is slight and gray and animated. He brought a binder of his lyrics with him, full of songs set down over the decades — so many, written so long ago, he can’t recite them by heart.

There are tunes about love and loss and faraway places, like a song from 1967 called “Je reviens Fanny.” Aznavour reads the lyrics from his binder. They translate to, “I had vagabond ideas when I was still a child / I wanted to go all over the world and see the Leeward Isles, the sea, and you.”

When Charles Aznavour travels these days, he brings his entourage: family and managers. The swank accommodations where we spoke are a far cry from his first visit to New York 68 years ago. He and a fellow performer had followed Piaf across the Atlantic, longer on hopes than on plans. Aznavour says they arrived without three necessities: “No visa, no money, no English.”

So, Aznavour was taken straight to a holding cell on Ellis Island to await deportation. He was ultimately sprung, and he got a room in a dive on Times Square. He describes himself as a streetwise young man who had survived the German occupation of Paris during World War II. He survived New York City using what little he had — including a nice pair of snakeskin shoes, which a man bought off of him for $50. “It was money in those days!” Aznavour says. “We had $50, we were able to eat.”

While Charles Aznavour became one of the most famous French performers of his day, he is also very proud of his Armenian heritage. His grandparents had fled the genocide in Turkey, and Aznavour now serves as Armenia’s ambassador in Geneva to both the Swiss and the U.N. institutions there. He has strong feelings about the current hostility toward immigrants in Europe.

France, he says, has typically embraced immigrants — like Picasso, from Spain, and Marie Curie, from Poland. “Picasso is French. Marie Curie was French. You know what I mean?” Aznavour says. “We are very proud to have those people, but we don’t want to have new.” To him, rejecting immigrants is “une erreur” — a mistake. “We must have them,” he says. “It’s important for the country, for the culture, for the kids, for everything.”

The son of immigrants, Aznavour became a very French type of entertainer — a pop singer-songwriter. He says his frank lyrics set him apart. “I said we can use every word, even the bad words, in a song,” he says. “Why not be free in songs when you have that in movies, in books, painting, sculpture?”

Aznavour makes no attempt to hide his age. He wore hearing aids when we talked, and he told me he approaches his current tour audience with the same openness. “The public has the right to know everything about me,” he says. “I tell them that I don’t hear well, I don’t see very well, I can’t memorize my songs so I have a prompter, I say my voice is terrible.”

It’s a closeness that Aznavour enjoys. “They’re close to me because they are my confidantes,” he says. “Public is my first love, my mistress, as my wife used to tell me.”