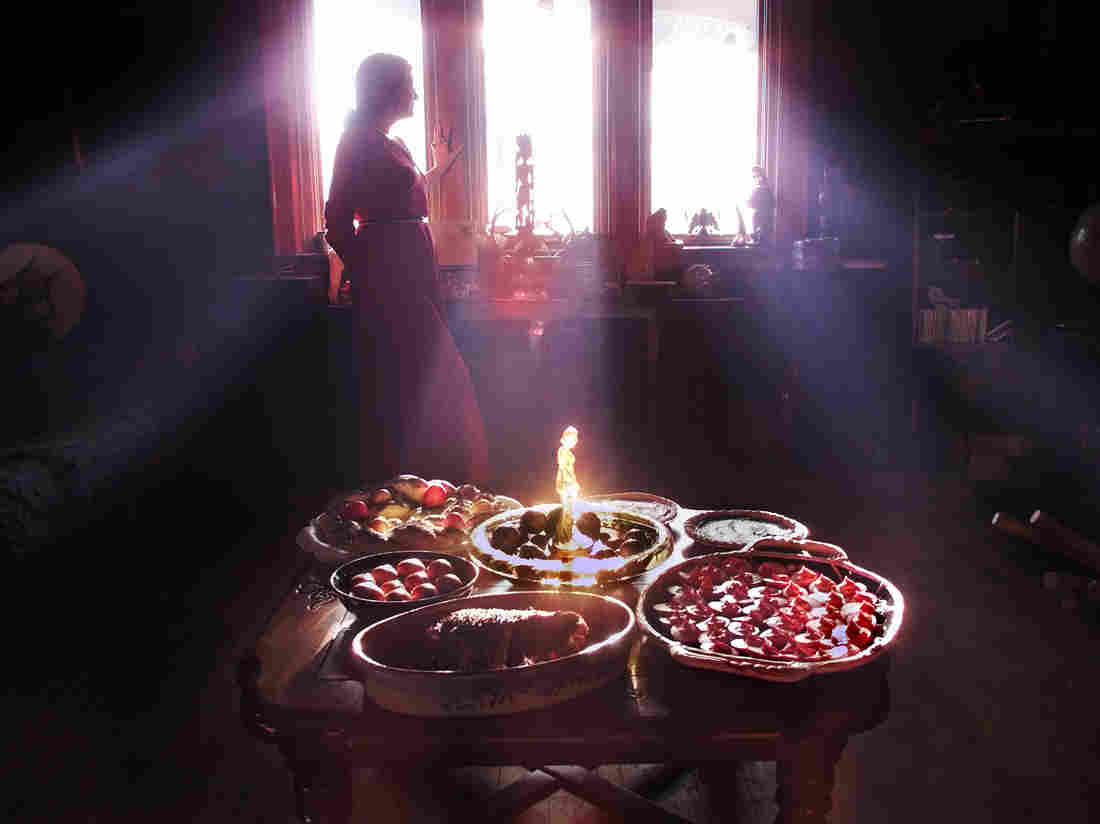

What The Real Witches Of America Eat

The bounty of the earth is celebrated in the high rituals of pagans. (Above) A Wiccan priestess is silhouetted by the afternoon light. In the foreground are examples of Wiccan cooking for the vernal equinox: (clockwise from near right) beat-pickled eggs; roast beef in tarragon; bowl of eggs boiled with onion skin wrap; bread with eggs; Ukrainian painted eggs; and apple crumble. Bernard Weil/Toronto Star via Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

Bernard Weil/Toronto Star via Getty Images

What do witches eat? If you’re thinking of blood and feathers and cauldrons bubbling with eye of newt and toe of frog, you couldn’t be more off-menu.

The correct, and disappointingly dull, answer is pizza, bread, fruit, nuts, granola bars, Cornish hens, Dunkin’ Donuts, Starbucks coffee, leg of lamb, beer, cheese, Merlot, frozen cheesecake and other supermarket comestibles.

The banal diet of the neighborhood witch is one of several stereotype-busting nuggets to be found in Alex Mar’s book Witches of America, an immersive first-person study of paganism in the U.S. Her book was preceded by a documentary called American Mystic. In the course of describing how and why Americans from different backgrounds and belief systems are drawn to the occult, Mar also reveals how food is used in the rites of contemporary witchcraft.

As part of a quest that fused spiritual self-inquiry with anthropological research, Mar, who describes herself as “an over-educated liberal New Yorker,” dove deep into pagan communities in San Francisco, Illinois, New England and New Orleans. Keen to find out if “even a piece of me skews magical,” she attended mega witch conventions, participated in exorcism exercises and dance revels, attended a Gnostic mass and a workshop on poisonous herbs, offered gumdrops to Santa Muerte (the popular Mexican folk saint of Death, who is known for her sweet tooth) and even trained briefly in witchcraft.

But she is candid enough to admit that when she started on this fascinating and unpredictable journey into the occult, she nursed similar prejudices about food and witchcraft.

“I’m half-Cuban, half-Greek from New York, and Greek cuisine includes octopus, tripe and sea urchin. So I’m quite used to foods that many would consider squeamish,” she told me. “But I still had the notion that witchcraft was performed with very repulsive ingredients. Somewhere in my subconscious, probably from the Brothers Grimm, magic is performed using raw animal parts and human blood. And yes, folk magic in some parts of the world does use animal parts and animal blood, but when it comes to everyday food, what witches eat is no different from what others eat.”

She discovered this early on in her research. One of the first witches Mar met was “Morpheus,” a skinny, redheaded pagan priestess in baggy jeans who welcomed her to her trailer in the Bay Area with “a pan of premade enchiladas.” Soon, Mar watched as carloads of witches drove up to an autumn equinox gathering at Stone City in the Bay Area (the hub of American paganism) armed with picnic gear — “baggies of herbs,” coolers, and “brown paper bags crammed with discount groceries.”

Witches of America is full of modern-day Wiccans and witches who Skype, drive pickups and drop off their kids at school. And though Mar did meet a young necromancer who “harvests” heads from a New Orleans graveyard, he is clearly an outlier.

Many witches keep their magic lives quiet and prefer to remain in the “broom closet,” coming out only to friends and fellow believers. Morpheus, for instance, is the alias used throughout the book for a woman whose day job is with the federal government. But she is also a respected Bay Area priestess who sings to the moon, and who dragged crushingly heavy stones down dirt roads to build a henge to The Morrigan, the Celtic goddess of war.

Since paganism has deep pre-Christian roots in nature worship and the harvest cycles, the bounty of the earth is celebrated in its high rituals.

At the very first pagan ritual Mar attended, Morpheus, dressed in fitted black velvet, presided as priestess at her self-built henge. Mar had watched her bake a bread sculpture of a sun god, lay it out on a dish and place “a dry ear of corn between his dough-legs” for a phallus. The figure was carried up the hill and laid out surrounded by pomegranates and apples, symbolizing the fertility of the earth.

Later, Mar watched Morpheus take two jars filled with cream and dark ale, the favorite foods of The Morrigan, and pour them out as offerings.

Today, the term “witch” is used to describe the nearly 1 million Americans who practice paganism. Once used as a derogatory term, the word “pagan” has been reclaimed and is used as a giant catchall, says Mar, “for people who practice a nature-worshipping and polytheistic religion, which has its own rites and rituals, just as any other religion has.”

“One of the things that impressed me was how practical pagans are,” says Mar. “If you could get an ingredient for a spell at a discount store, that was fine. It was better to be serious about your practice than spend the whole weekend going into the woods looking for an herb that can be found in the produce section of Whole Foods.”

Where food has a starring — and endearing — role to play is at Samhain (pronounced SAH-win), the major pagan holiday, which coincides with Halloween. Pagans believe that at this time of the year (from late October into early November), the veil between the worlds of the living and dead is thinnest, and therefore the best time to commune with one’s dead ancestors and loved ones. And what better way than to break bread with them?

“At these Samhain gatherings, many witches will dance and drink and eat the things the person they are remembering enjoyed,” says Mar. “The belief is that you can channel physical pleasure to the dead person, you can invite them to come closer and taste their favorite foods for that one night. If, say, you had an aunt who was partial to cherry pie, you would leave one out for her. Some witches drink whisky for the deceased who loved a good whisky. I find this aspect of the pagan community very moving — the fact that foods you consider everyday can be made into an offering, not just the ceremonial foods like a chalice of red wine sanctified by the church.”

Perhaps the one area where popular fairy-tale notions of food and witchcraft match the reality is in the casting of spells, something Mar learnt firsthand. Finding herself in the coils of boyfriend trouble, she asked Morpheus, by then a friend, for a “binding spell” to protect her boyfriend from the “emotional voodoo” of his former lover.

Morpheus emailed back with a Freezer Spell that involved buying a cow’s tongue from the butcher, slitting it open, inserting something representative of the ex-lover, like a photograph, and writing out what Mar wanted to do to her. Then, instructed Morpheus, dress the photograph with “any mixture of these things: mustard (for disruption), red and black pepper (to make ill words burn in her mouth), cloves or slippery elm bark (against malicious talk), and the most important one, alum, to stop her tongue.” Finally, sew or pin up the tongue, wrap it in foil and stick it in the freezer.

And so Mar drew up her shopping list. But that’s about as far as she went. “I was a little bit self-conscious about it,” she says. “Sewing up a cow’s tongue and chanting over it was too dramatic, and I hesitated.”