National Science Test Scores Are Out, But What Do They Really Tell Us?

LA Johnson/NPR

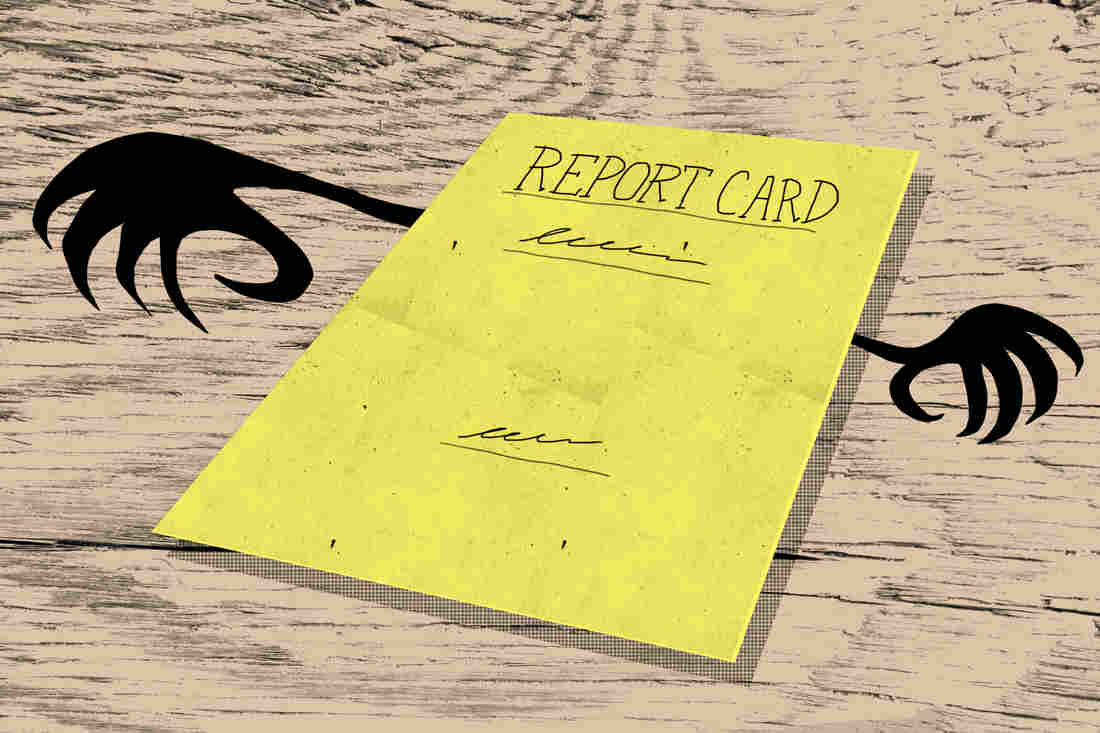

The National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, is called The Nation’s Report Card for good reason; the tests are administered the same way year after year, using the same kind of test booklets, to students across the country.

That allows researchers and educators to compare student progress over time. NAEP tests serve as a big research project to benchmark academic achievement in subjects like science, math, reading, writing, civics, economics, geography and U.S. history.

Science results were out Thursday for 4th, 8th, and 12th graders.

Among seniors, achievement was flat, and performance gaps by race, ethnicity and gender persisted.

But fourth- and eighth-graders showed modest progress: each up four points since 2009.

That’s encouraging to U.S. Secretary of Education John King, who said in a press call, “We’re seeing racial achievement gaps in the sciences narrowing in the fourth and eighth grades … and the gender gaps also are closing.”

“All of this means that more students are developing skills like thinking critically, making sense of information and evaluating evidence,” King said.

The results got us wondering about the bigger picture: How well can a multiple-choice and short-answer test assess a subject as complicated as science?

We reached out to science education experts to help us answer that question.

Illustrated portrait of Nobel Laureate, Carl Wieman LA Johnson/NPR hide caption

toggle caption

LA Johnson/NPR

Carl Wieman is a Nobel Laureate who teaches in Stanford University’s physics department and Graduate School of Education. He’s an advocate for quality active learning in science classes: limiting lecture and textbook time in favor of small-group problem solving, with the teacher as coach.

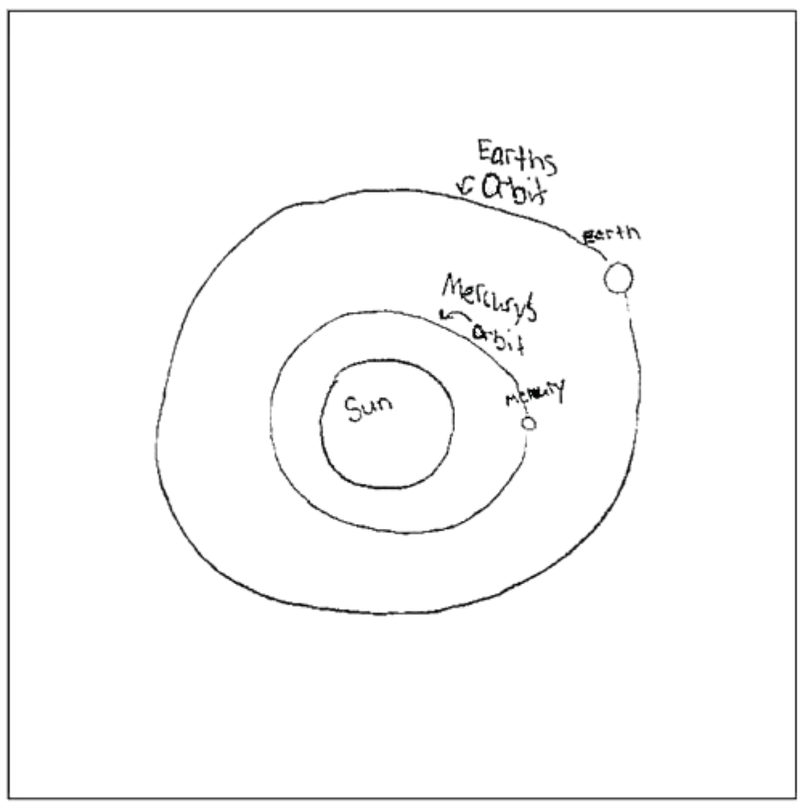

He took a look at some sample questions we sent to him, saying many of them are shallow, asking for recall of terminology or facts.

“I’ve seen worse,” Wieman tells us. “A lot worse.”

Still, he’s not convinced the NAEP science tests meaningfully assess scientific thinking.

“There is no concept at all of where a student might be able to use those facts or have any relevance in anyone’s life, which for me is kind of more meaningful measures of learning.”

Sixteen states are in the process of adopting science standards that try to get students to think and ask questions just as scientists, engineers and physicists would.

Question 2: Mercury is the planet closest to the Sun. In the box, draw a diagram showing each of the following: Earth, Mercury, Sun, Orbits. Label all parts of your diagram. National Assessment of Educational Progress Sample Questions hide caption

toggle caption

National Assessment of Educational Progress Sample Questions

They’re called Next Generation Science Standards; they’re research-based, and de-emphasize the classic lecture, textbook, lab and test model of science teaching.

Wieman says NAEP is missing a chance to help redirect science learning. “I see a real disconnect between these kinds of questions and what’s called for in the standards.”

David Evans is the executive director of the National Science Teachers Association, which has been instrumental in creating the new science standards. His organization calls for “a dramatically more active learning process.”

This means students should be “confronted with a phenomena, asked to develop their own questions, and engage in the practices of science.”

But how do you check students’ progress in this complex process? “Assessment is a real challenge,” Evans says. The National Academy of Sciences released a report that recommended states start with classroom-level performance assessments. But, says Evans, it’s early days; national, benchmarked assessments don’t yet exist. “No one has actually developed tools that the community feels comfortable with for assessing student progress under the new standards,” he says.

Dale Dougherty, is founder of MAKE: magazine and the Maker Faire, which emphasizes hands-on learning and exploration in science, technology and engineering.

He says too many schools still ask students to label, say, the parts of a microscope for a test, but fail to teach students how to use one to see something new. In line with the National Academy of Sciences, he’d like to see schools make a bigger shift toward portfolio-based assessments. That’s where a teacher evaluates projects, individual and group presentations, reports, papers and other work collected over time.

“It’s closer to how the work world evaluates people, which is: ‘What is it you can do? Not just what do you know.’ And I think that’s an important shift,” Dougherty says.

Jennifer Childress is the director of instructional support for science for Achieve, a group that works to improve state assessments and learning standards and also helped create the Next Generation Science Standards. Childress says that NAEP today is better than nothing. “The NAEP results are likely to give us a good indicator of how students are doing on science skills and practices.”

And that was a common theme throughout our interviews. There may be value in NAEP because of its history, even if it’s not perfectly aligned to the future.