A Moment Of Silence For The Black And Brown Talent That Grew On Vine

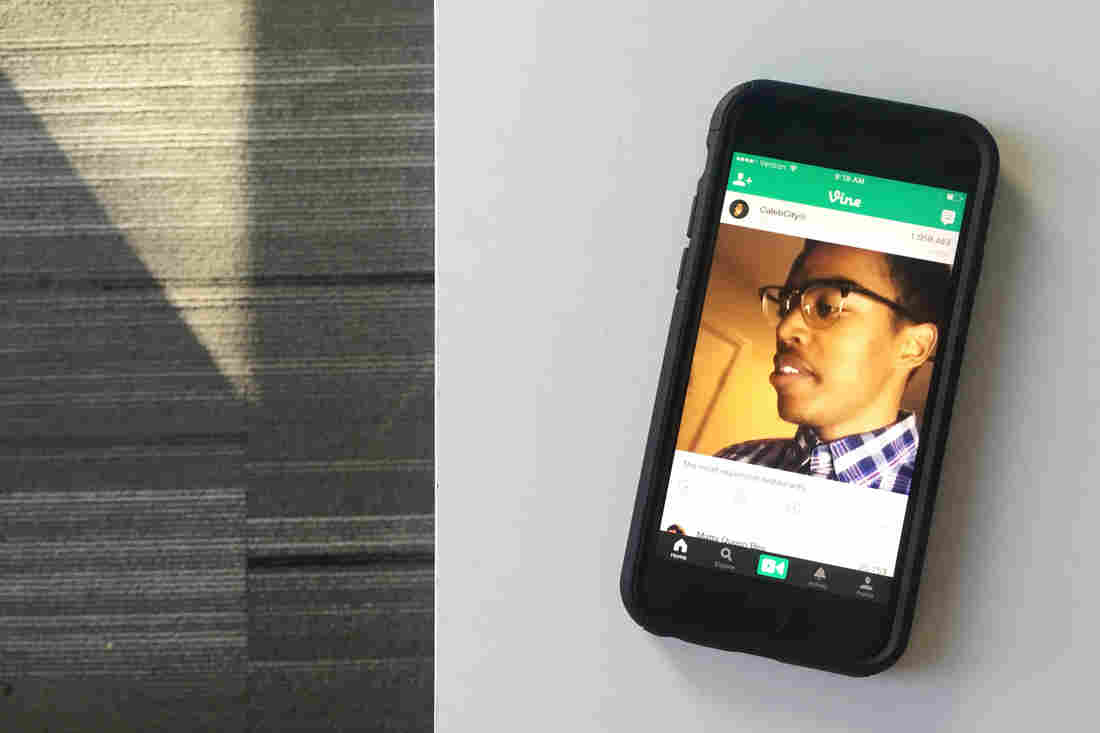

Vine user CalebCity pokes fun at the spare dishes presented in fancy restaurants. Twitter announced this week that it’s closing the video app. Emily Bogle/NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Emily Bogle/NPR

A girl fights a Pokemon character in a parking lot and gets sucked into a Poke Ball. A mustachioed man, pretending to be El Chapo, runs through a cave, then a fast food restaurant and then a mall in search of Donald Trump, whom viewers see video of making denigrating comments about Mexicans. A young man satirizes the spare dishes presented in fancy restaurants.

These are the types of wacky, of-the-moment videos that will be missed now that Twitter is winding down its video app, Vine. (To be clear, Vine says it won’t delete its videos. As least, for now. They will be preserved for your perusal, and users will be able to download their own videos.)

And though people all across the Internet are eulogizing Vine for its “mirthful” videos and for the gaping six-second hole it’ll leave in our collective hearts, this is also a particular loss for young people of color. Vine is home to a distinctly younger — and browner and blacker — user base. According to a Pew Research Center survey last year, almost a quarter of teens used Vine; and of those surveyed, 31 percent identified as black (non-Hispanic) and 24 percent as Hispanic.

In its short lifetime, Vine became a powerful platform for protests over police-involved shootings. Black and brown activists shared videos from places such as Ferguson, Mo., providing a visceral understanding of those events.

Vine was especially crucial for incubating black talent and launching careers.

Hannah Giorgis wrote last year for The Guardian about Vine’s alternative pipeline. “At a time when barriers to entry in Hollywood and formal creative industries continue to be almost insurmountable for black media-makers,” Giorgis wrote, “the ability to simply record a video with one’s phone and share it widely presents a more widely accessible opportunity for creative ingenuity.”

And Vine’s shareable “cultural ecosystem” made it easy for videos to become explosively popular. For instance, Giorgis wrote, this allowed black Viners to “[birth] countless memes and accompanying sociolinguistic phenomena, from ‘or nah’ to ‘hoe don’t do it’ to ‘do it for the vine‘.”

Earlier this year, Latoya Peterson at Racialicious presciently hinted at the app’s demise, saying that with Twitter’s takeover of the app, its future “[hung] in the balance.” Still, Peterson argued, Vine was powerful for its “uncensored performance, play, rejection, and complication of race and gender on the platform.”

Peterson wrote in great depth about the window Vine provided into how its users were grappling with race in unvarnished, unchecked ways, as they poked fun at racial misunderstandings and awkwardness, showed the boundaries of saying the N-word and attempted to spear tropes or flip racial stereotypes on their heads. Though, Peterson cautioned, maybe not very successfully, as many seemed to walk the line between racist and commentary.

All of this — Vine’s experimental nature — made the platform so fascinating.

To quote this old Vine from user bigzeekTV: Vine, “Fly away. And be at rest.”

#RIPVine.