With GPS And Graph Paper, Farmers Find A-maze-ing Ways To Bring In Cash

The theme of Mike’s Maze this year is “See America,” which commemorates the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service. Courtesy of Warner Farm hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Warner Farm

In the small town of Sunderland, Mass., is a 300-year-old, family-run plot of land that fuses fine art and farming.

Mike Wissemann’s 8-acre cornfield maze is a feat of ingenuity, with carefully planned and executed stalk-formed replicas of notables such as the Mona Lisa, Albert Einstein and Salvador Dalí.

But how do those pictures come to life? Maybe you remember Skill-o-Gram puzzles, in which the clues are squares that have labels like A-4 or F-5, each one holding part of the design. When those parts are copied into a blank grid, they create a whole picture.

Corn is also planted on a grid. By breaking the field into squares on paper or computer, each one holding a piece of the picture, and scaling up, you’ve got a blueprint. But in a cornfield, the picture is pixelated, so it’s kind of like creating a giant halftone photo, using the density of the corn to make the image darker or lighter.

Charles Darwin and his evolutionary finches were the theme of Mike’s Maze in 2009. Courtesy of Warner Farm hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Warner Farm

For the past 17 years, Wissemann’s family and landscape artist Will Sillin have used arithmetic as well as the tools and technology available to them. In 2000, that was graph paper and an ATV equipped with a GPS that was not very accurate. But now, a GPS-equipped mower can zoom in on a single stalk within an inch. Add in a drone and you’ve got yourself an elaborate maze.

Wissemann’s daughter-in-law, Jess, has designed the maze for the past two years. She studied art history in college and likes to use that background when she creates her designs in Adobe Illustrator. She sends that design, scaled to the Wissemanns’ cornfield, to Rob Stouffer, who owns “Precision Mazes,” based in Missouri. Stouffer cuts mazes all over America.

“He plots it in his tractor’s GPS system. The design is overlaid on his screen. So as he moves through the field, the cutters can track where he is,” says Jess. “It doesn’t actually guide him, though. He still has to navigate to make sure he’s really precise.”

The tractor has reduced the time it takes to cut a maze from a month to a single day. But even new, high-tech equipment has its limits, the biggest one being that the mower can cut no narrower than 5 feet.

“If I want to do any really detailed areas, I have to keep in mind that I’m the one that’s going to have to go out there and cut down the stalks by hand,” says Jess.

Mike’s Maze from 2005 was an homage to Albert Einstein and his spiral galaxy. Courtesy of Warner Farm hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Warner Farm

Which she does. She grabs hold of a stalk and starts shaking. A drone sends that video to her on the ground in real time, so she can zero in on which stalks need cutting to form the most accurate picture. This technique allows her to use special fonts or to home in on the pupil of an eye.

Even one stalk can make a difference. “The mazes that have lettering in them, if you take out a stalk, there’s going to be a gap,” Jess says. “So I go stalk by stalk: Is this the right one to pull out?”

The Wissemanns use non-GMO seed corn, which is used to feed animals. When the field is harvested in November, the family also uses the crop to feed the corn furnace that heats the farm’s greenhouse.

During harvest, the maze gets chewed up by the combine, which separates the ears of corn from the stalks.

Isn’t it painful to watch such a masterpiece get razed? “I don’t worry about it too much,” says Jess. “If I were worried, I wouldn’t want anyone to walk through it, because we have more than 25,000 people every year, and they are really the ones that destroy it.”

But they sure have fun when they do. The maze supplies about a third of the farm’s income.

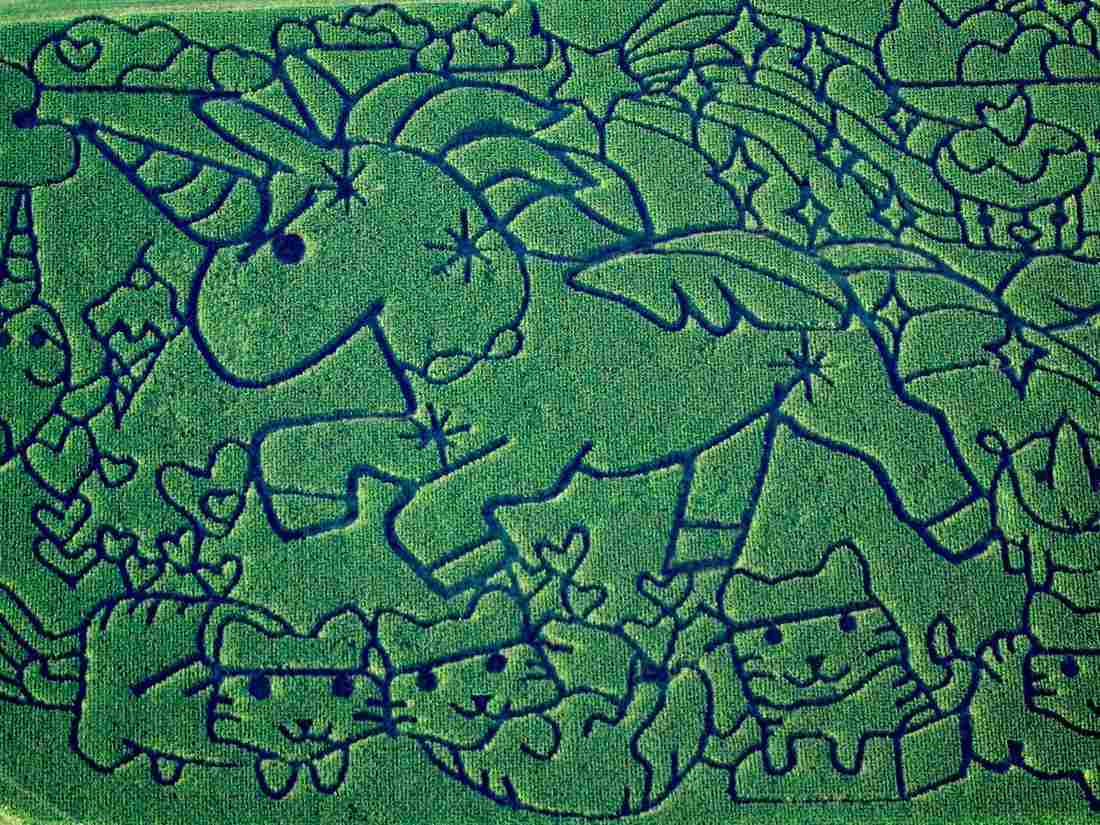

Inspired by cute images on the Internet, Angie Treinen designed a maze full of unicorns, kittens, narwhals and rainbows. Courtesy of Treinen Farm hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Treinen Farm

“We farm 150 acres, and the maze is only 8 acres. So the return per acre of the maze is pretty phenomenal,” Jess says. “It’s been a crucial way to diversify our farm.”

This year’s maze is called “See America” and commemorates the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service. The image shows water and steam bursting from Yellowstone’s Old Faithful geyser and morphing into the face of Teddy Roosevelt, who created five national parks. The design is based on Works Progress Administration posters from the 1930s and ’40s.

At Treinen farm in Lodi, Wis., the maze’s theme and method are much different. Designer Angie Treinen was inspired this year by all of the cute things she found on the Internet: ninja kittens, cupcakes with faces, unicorns, narwhals and rainbows. Her style is based on the Japanese art style known as “Kawaii,” which means “cute.”

Treinen’s is a century-old, family-run farm. About 15 of the farm’s 200 acres are devoted to the corn maze. Here, maze cutting is still designed and executed the old-fashioned way, by using a lot of graph paper and elbow grease.

The Treinens do not use GPS or a professional maze cutter.

Treinen Farm brought Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man to life in its 2012 corn maze. Courtesy of Treinen Farm hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Treinen Farm

“We’re always afraid that if we made the jump to using GPS technology, that our complex designs would not be as accurate as we wanted them to be,” says Treinen. “And like many small businesses, we can only afford to do everything ourselves,” she adds.

The Treinens enlist the help of family and hire kids from the local high school to carve about 5 miles of trails into the corn. The process takes about three days, usually during the hottest part of June.

Treinen’s husband, Alan, plants the corn in rows about 30 inches apart in both directions to make a grid. “I put a grid overlay on the design that corresponds to the field,” says Treinen, who creates her images on the computer. “Each square on my plan is 15 feet in the field.”

The cutting crew then stakes the field. “Once it’s ready, you can count the stakes and flags and rows, and find where you are in the field relative to the design on the page at any point. It’s really just counting: I’m this many rows in and I’m this many feet in … so I must be at this point,” Treinen says.

The maze can be cut as soon as the corn plants are visible, even if they’re only 3 inches high. Corn grows fast in June, and by the time it’s knee-high, the leaves have spread out so much that the rows are covered. When the corn is short, the cutters are able to look across the field like a surveyor.

“They’re literally marking with spray paint on the dirt or the corn plant,” Treinen says. “They’re not even cutting the actual stalks of the corn; they’re marking a trail. We till that corn out. Then the maze just grows up.”

The maze-cutting in Lodi has become a tradition in the community.

Treinen Farm’s 2013 Kraken maze was full of lots of “tenterrific” places to get lost. Courtesy of Treinen Farm hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Treinen Farm

“This year, the maze was cut mostly by teenagers, and some kids as young as 12 or 13. The lead cutter is a little bit older; it’s his responsibility to make sure each trail is where it needs to be. I’m amazed at how good a job these really young people do,” Treinen says.

Unlike the Wissemanns, the Treinens use genetically modified corn. “It reduces the amount of pesticides that we would need to spray to keep the corn healthy,” Treinen says. “And we need corn that is not going to fall down. We’re using a variety of corn that has really good stalk strength and standing power, and that comes from the genes that it has in it.” The Treinens also like the corn to stay green for as long as possible, because they feel the bushiness contributes to a good maze.

In November, they harvest the corn and sell it to local farmers or on the commodities market.

The Treinens’ farm makes 90 percent of its income from agro-tourism: the maze, the pumpkin patch and hayrides. It is a working farm, but a small one that grows just corn, soybeans and hay.

“The land we have is not nearly enough to support a family on if we were just growing crops,” Treinen says. “Agro-tourism has allowed us to keep the farm viable.”

Mazes, first called labyrinths, date back 4,000 years and were used for rituals and processions instead of entertainment. Throughout the centuries, mazes began to appear in gardens of castles and wealthy estates. They evolved into a game in which people would try to find their way into the center and back out again.

It was only a matter of time before someone thought of adapting that idea to a cornfield. That person was Don Frantz. On a cross-country flight, he looked down over the farms of the Midwest and saw crops planted in perfect, amazing contoured lines. What would it take to transfer the concept of an English garden maze into something uniquely American, using a field of corn?

In 1993, Frantz launched the first modern corn maze, designed just for fun: the dinosaur-shape “Amazing Maize Maze,” in Annville, Pa. His concept was successful.

And while technology continues to transform the art of maze-cutting, the idea itself remains firmly planted: Wandering through a corn maze has become one of America’s favorite autumn rituals.