Volume 3 Of Eleanor Roosevelt Biography Chronicles The Rise Of An Activist

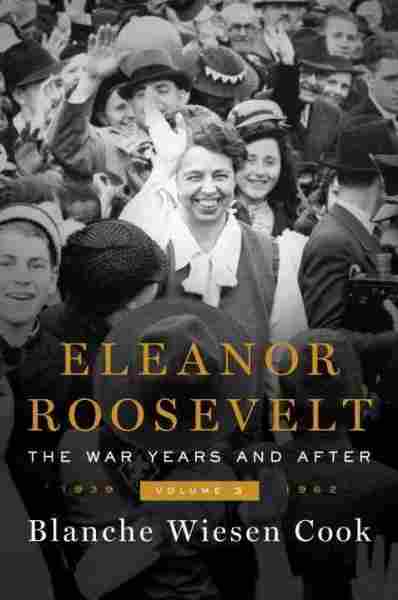

Eleanor Roosevelt, shown here in London in 1959, continued to work on behalf of progressive causes after her tenure as First Lady ended. J. Wilds/Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

J. Wilds/Getty Images

Last things first. One of the most extraordinary aspects of the third volume of Blanche Wiesen Cook’s monumental biography of Eleanor Roosevelt is the way it ends. I don’t think I’ve ever read another biography where the death of the subject is noted in an aside of less than 10 words, on the second to last page of the book.

Bear in mind that, with this third and concluding volume, Cook has devoted almost 2,000 pages to Eleanor’s life. Yet, she compacts her subject’s post-White House years into a brief “Epilogue” and says nothing about the personal struggles that Eleanor faced as a widow, or the physical challenges she contended with as she aged.

Cook doesn’t even mention the cause of Eleanor’s death on Nov. 7, 1962. You have to look elsewhere to find out that she was ill for the final two years of her life and that tuberculosis was the culprit.

This abrupt ending to a biography whose publication has stretched over almost a quarter of a century speaks to both Cook’s priorities, as well as to Eleanor’s. In earlier volumes, Cook described Eleanor’s emotionally deprived childhood and delved into the complex marital partnership that evolved between Eleanor and Franklin. Cook also explored what she controversially identified as an erotic friendship between Eleanor and reporter Lorena Hickok.

But her primary concern as a biographer has been on Eleanor’s growth into a savvy, impassioned activist, particularly on behalf of New Deal programs and civil rights; in this volume, the reach of Eleanor’s activism expands to refugee rescue and the founding of the United Nations.

Privately, Eleanor continued to battle bouts of depression that she had suffered most of her life — she called these episodes her “Griselda moods.” But, you get the sense in this final volume of Cook’s biography, that Eleanor, as she grew into the towering role of “First Lady of the World,” was more determined than ever to keep herself so engaged, that even death, when it came calling, would have to take a number and wait.

Cook’s particular focus here is on the war years, when, as she succinctly explains, the partnership between Eleanor and Franklin shifted as the president turned away from his domestic programs:

In the past, [Eleanor] had gone to the public to argue on behalf of FDR’s New Deal programs ,… to build support for things a reluctant and divided Congress tried to hobble. Now … [Eleanor] increasingly went to the public to argue for her own version of what was right and essential.

Eleanor’s homeland concerns (like fair housing laws and the relaxing of quotas on immigration) ensured that she and her so-called “pink pals” would be constant targets of anti-Communists. “To know me is a terrible thing,” Eleanor commented after a particularly ruthless episode in which friends had to resign from an arts-and-education program she championed.

When America entered the war, Eleanor traveled to Blitz-ravaged London and flew across the Pacific to visit servicemen in Bora Bora, Samoa and Guadalcanal. Even there, she continued her campaigns against racism, visiting and shaking hands with “Negro” servicemen.

Cook quotes the recollections of a black army private who was eating an ice cream cone when Eleanor appeared in the canteen. “[S]he looked straight into my eyes and said, “May I have some of that ice cream?” According to his account, Eleanor took a big bite of the cone and handed it back to him.

Cook doesn’t elaborate, so without further digging, there’s no way to tell whether reporters were trailing Eleanor at that moment or whether it was a simple act of human connection between a First Lady and a serviceman. Either way, it was a radical gesture for that age.

Volume 3 of Cook’s biography of Eleanor is packed with many other revealing small incidents, as well as detailed accounts of her tireless work on behalf of progressive causes. (The list of committees alone that claimed Eleanor as a chair or active member could constitute an entire chapter here.)

I’ve read all three volumes of Cook’s biography and, taken together, they present an exhausting and exhilarating story, as well as undeniably melancholy one. In her relentless efforts to push American democracy to fulfill its promises, Eleanor Roosevelt was ahead of her time. As we ponder our curdled political culture on the eve of Election Day, it’s not at all clear that we have yet caught up to her.