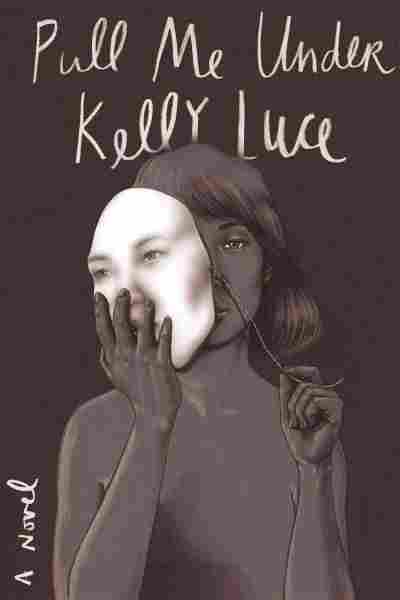

Coming To Terms With A Bloody Past In 'Pull Me Under'

I have some problems with Kelly Luce’s new book Pull Me Under, and I’ll get to those. But first I want to say that this is a suspense novel with a female protagonist that gets more right about women than so many others I’ve read in the past few years. Note there’s no use of “girl” in the title, even though a great deal of the book concerns the childhood and adolescence of one. We learn about that girl’s darkest secret on page one, in a 1988 “excerpt” from “Kyoto Wow! English-language news magazine, October 14, 1988.” It seems on that day, in the Japanese city of Tokushima, a 12-year-old girl named Chizuru Akitani showed up in her school’s staff room covered in blood that she said was not her own.

Rio Silvestri, that powerful female protagonist, narrates her own story, including the years in which she was known as Chizuru Akitani, daughter of Living National Treasure violinist Hiro Akitani. And Rio, we will learn quickly, calls her heart “the black organ.” She’s got issues, serious issues, that caused her to leave the Japan where she grew up for education and adult life in Colorado. And she spent ages 12 through 20 at Kawano Juvenile Recovery Center for that blood-spattered incident that occurred just a month after her beloved mother Elana killed herself.

Elana, a beautiful and gifted artist, happened to be Anglo-American — so Chizuru was known throughout elementary and middle school as hafu, meaning half-breed. Worse, she was overweight, and her classmates called her names like “Fatty Potato.” One of my problems with this unusual and affecting novel is that it takes far too long for us to learn about the more serious bullying Chizuru endures. It makes sense that Luce might want to build tension, but by the time we learn Chizuru’s fuller story, readers have lost the delicate threads that connect this troubled young woman with her powerful adult self.

When we meet the reinvented Rio, her celebrated father has died and left her an unusual legacy consisting of his violin bow, a banknote folded into an origami crane, and a letter written in Japanese she can no longer decipher. A registered nurse, Rio is happily married to a doctor named Sal, with whom she has an 11-year-old daughter named Lily. But she still has issues, and she tells us that she keeps them and her “black organ” under control through running. Not just any running; Rio isn’t jogging through a series of holiday 5K races. She’s pushed beyond marathons to do “ultras,” endurance courses that can involve 60 miles or more. Some of the writing about Rio’s self-punishment through gross-motor exercise is the most interesting in the book. Luce fully understands the pleasure-pain dynamic involved in pushing yourself past limits:

You can’t run 50 kilometers nonstop. No one can. So you have to build in periods of walking … It took me a long time to give in to the fact that I would have to walk briefly in order to run farther. The hardest part was intellectual; an ultra is purely physical, the reason I had gotten into running in the first place. This was about getting my mind to a place where it knew when to listen to its body but also when to pat its head like a good, obedient child.

So much about this passage resonates after you’ve read Pull Me Under. Rio has been running from Japan, from Chizuru’s deeds, and from her own self for so long that she’s gotten her mind to a place where it behaves like the good, obedient child her home culture wanted. (There’s a chilling passage when Chizuru is “allowed” to leave for college in the United States; a Japanese judge tells her that she is “an expense to this nation … Thus far in life all you have done is take … But what have you given back?”)

That resonance is what I found most difficult about the middle section of the book, in which Rio reunites with her beloved teacher “Ms. Danny,” an expatriate Kiwi. Danny’s plan to make an 80-temple pilgrimage hike pulls Rio in — and it might have made for a truly scary denouement. Instead, Luce pulls the story back and makes it about a flip side of death. While that scenario is moving, it never properly connects back to the original death in the book, that of Rio’s mother.

However, the novel’s ending, in Japan, and with a family that gives new meaning to “the kindness of strangers,” does connect to Rio’s running and to her body in a satisfying way. While we know that Rio is fit and shapely from running (one of her friends tells her “you’ve got that line,” referring to her quadriceps), we don’t know much about how she looks — and that’s perfect, because she is not concerned with being pretty or attractive. Rio Silvestri has learned to live in her body, not just use it as an escape mechanism. She and Sal and Lily wind up not pulled under, but bound more tightly together by Rio’s clear look at her troubled past.

Bethanne Patrick is a freelance writer and critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.