I Shall Faint: 'Unmentionable' Unpacks Victorian Womanhood

Victorian manners occupy a space both sublimely funny and quietly horrific. With deeply specific and often counter-intuitive advice, Victorian pundits attempted to establish class markers and prescribe “acceptable” behavior that tended to come down harder on women than on men.

How specific and stifling? When at a dinner party, a lady eyeing the dessert course would have to hope a man was willing to cut her pear for her, as she was implicitly discouraged from doing it herself.

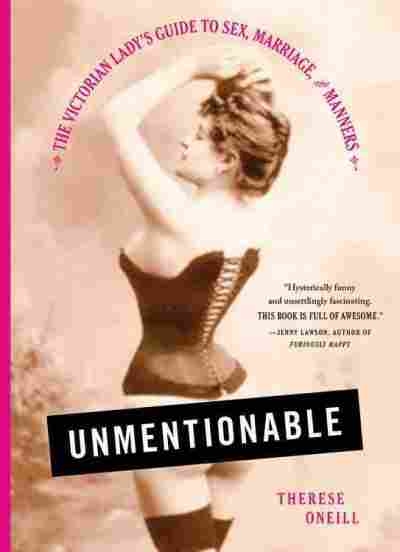

In theory, such ridiculous particulars were merely a level of Byzantine minutiae that haunted the rich and idle; most modern folk manage to get by without knowing the details of private-jet etiquette. In reality, however, this obsession with propriety affected all women, stifling open communication and often hindering women’s access to education, marital rights, and health care. Even the ideal parameters of a woman’s period were dictated to her, often on the authority of writers who weren’t even doctors. This fascinating and ongoing hypocrisy is what Unmentionable: The Victorian Lady’s Guide to Sex, Marriage, and Manners hopes to unpack.

Therese Oneill has built a byline deconstructing the Victorian mindset for venues like Mental Floss and The Atlantic, and it’s clear in every page of Unmentionable that she’s done her research on what the Victorian lady was expected to tackle, from dinner-party etiquette to arsenic as skin care. As a historical primer, it would have big shoes to fill; if research is all you’re after, Ruth Goodman’s already taught us exactly How to Be a Victorian, in an exhaustively informative day-to-day take on 19th-century life. But Unmentionable largely avoids setting itself up for comparison; its focus is narrower, and its approach baldly editorial. Presenting the surreal and infuriating past is not enough — the vagaries of courtship, running a household, and taking a bath fall under a modern and distinctly snarky lens.

There’s perhaps never been a better time to snicker a little at what’s come before us; Hamilton, Kate Beaton, Horrible Histories, and Drunk History have all laid plenty of groundwork for turning the Good Old Days into a cabinet of morbid curiosities. And the tone behind Oneill’s premise — that she’s an omnipotent force that’s knocked the reader back in time and is maintaining a very personal line of communication as she shows you around — will likely make or break the reading experience.

Some of the irreverent observations hit a suitably dry remove, as in her introduction to Orson Squire Fowler, “a phrenologist. A word that sounds doctor-y, but many words do. Like ‘timbrologist,’ which is an old word for stamp collecting, a pastime that holds as much medical influence as that of phrenology.” Other asides tilt so forcibly toward Casual Fun that the authorial voice threatens to knock you straight out of the book.

If you find the tone hard to take, then Unmentionable becomes both a glimpse into history and a case study in whether details of the Victorian gray market for birth control are interesting enough to carry you through strained interludes about the language of fans. (The style feels particularly awkward whenever Oneill touches on topics like slavery, for which this tenor of quick, snarky asides is ill-advised.)

But there’s enough research here to entertain a Victorian newcomer; for readers looking for a primer on their more baffling habits, this could be a good place to start — if young ladies are going to gnaw on their umbrella handles in the street, you might as well find out about it.

Genevieve Valentine’s latest novel is Icon.