Beyond The Pail: NPR Unpacks The History Of The Lunch Box

A Spider-Man lunch box on duty at Payne Elementary School in Washington, D.C. Kat Lonsdorf/NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Kat Lonsdorf/NPR

Our Tools of the Trade series is exploring some of the icons of schools and education.

It was made of shiny, bright pink plastic with a Little Mermaid sticker on the front, and I carried it with me nearly every single day. My lunch box was one of my first prized possessions, a proud statement to everyone in my kindergarten bubble: “I love Ariel.”

(Oh, and it held my sandwich too.)

That clunky container served me well through first and second grade, until the live-action version of 101 Dalmatians hit theaters, and I needed — needed — the newest red plastic box with Pongo and Perdita on the front.

I know I’m not alone here — I bet you loved your first lunch box, too.

Lunch boxes have been connecting kids to cartoons and TV shows and superheroes for decades. But it wasn’t always that way.

Lunch pails in a rural school, Wisconsin, 1939. John Vachon/Library of Congress hide caption

toggle caption

John Vachon/Library of Congress

Once upon a time, they weren’t even boxes. As schools have changed in the past century, the midday meal container has evolved right along with them.

Lunch In The Time Of Pails

Let’s start back at the beginning of the 20th century — the beginning of the lunch box story, really.

While there were neighborhood schools in cities and suburbs, one-room schoolhouses were common in rural areas. As grandparents have been saying for generations, kids would travel miles to school in the countryside (often on foot).

“You had kids in rural areas who couldn’t go home from school [for lunch] because it’s just too hard to get back and forth, so bringing your lunch wrapped in a cloth, wrapped in oiled paper, in a little wooden box or something like that was a very long-standing rural tradition,” says Paula Johnson, food history curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

This tin-plated steel lunch box was manufactured by the Ohio Art Company in the 1920s. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of the National Museum of American History

City kids, on the other hand, went home for lunch and came back. Since they rarely carried a meal, the few metal lunch pails on the market were mainly for tradesmen and factory workers.

After World War II, a bunch of changes reshaped schools — and lunches. More women joined the workforce. Small schools consolidated into larger ones, meaning more students were farther from home. And the National School Lunch Act in 1946 made cafeterias much more common.

Still, there wasn’t much of a market for lunch containers — yet. Students who carried their lunch often did so in a re-purposed pail or tin of some kind.

The Year Of The Lunch Box

And then everything changed.

The year: 1950. You might as well call it the Year of the Lunch Box, thanks in large part to a genius move by a Nashville-based manufacturer, Aladdin Industries.

The company already made square metal meal containers, the kind workers carried, and some had started to show up in the hands of school kids (lunch pail, meet lunch box).

But these containers were really durable, lasting years on end. That was great for the consumer, not so much for the manufacturer.

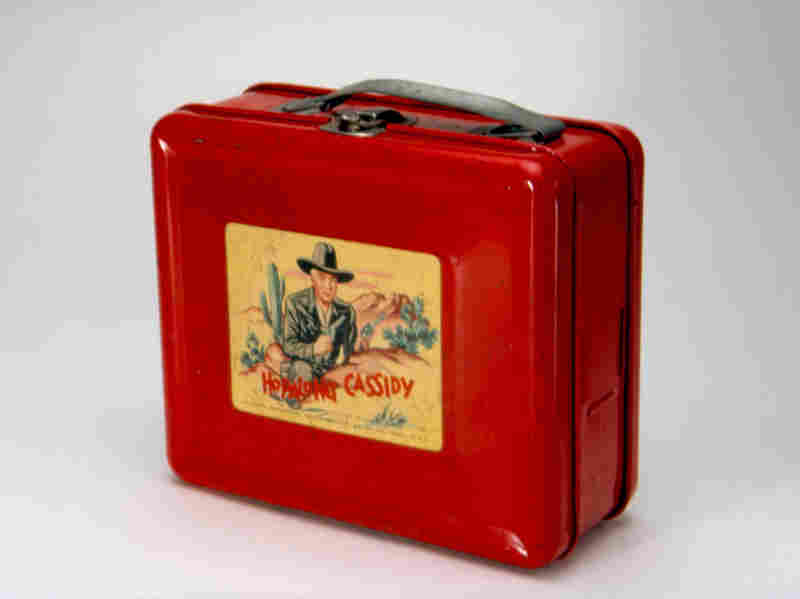

This steel lunch box, made by Aladdin Industries in 1950, was the first to bear a licensed image, and helped Aladdin launch a new product line that would last for decades. Hopalong Cassidy was a popular TV, radio and comic series. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of the National Museum of American History

So executives at Aladdin hit on an idea that would harness the newfound popularity of television. They lacquered lunch boxes with striking red paint and added a picture of TV and radio cowboy Hopalong Cassidy on the front.

The company sold 600,000 units the first year.

It was a major “Ah-ha!” moment, and a wave of other manufacturers jumped on board to capitalize on new TV shows and movies.

“The Partridge Family, the Addams Family, the Six Million Dollar Man, the Bionic Woman — everything that was on television ended up on a lunch box,” says Allen Woodall. He’s the founder and curator of the Lunch Box Museum in Columbus, Ga.

“It was a great marketing tool because [kids] were taking that TV show to school with them, and then when they got home they had them captured back on TV,” he says.

And yes, you read that right: There is a lunch box museum, right near the Chattahoochee River. Woodall has more than 2,000 items on display. His favorite? The Green Hornet lunch box, because he used to listen to the radio show back in the 1940s.

The new trend was also a great example of planned obsolescence, Woodall adds. Kids would beg for a new lunch box every year to keep up with the newest characters, even if their old lunch box (So long, Ariel!) was perfectly usable.

The metal lunch box craze lasted until the mid-1980s, when plastic (and for a short time, vinyl) took over. Two theories exist as to why.

The first — and most likely — is that plastic had simply become cheaper.

The second theory — possibly an urban myth — is that concerned parents in several states proposed bans on metal lunch boxes, claiming kids were using them as “weapons” to hit one another. There’s a lot on the internet about a state-wide ban in Florida, but a few days worth of digging by a historian at the Florida State Historical Society (thanks, Ben DiBiase!) found no such legislation.

Either way, the metal lunch box was out.

(Want to know more about that Golden Age of metal lunch boxes? Check out this episode of the Mystery Show podcast, that goes deep, deep down a lunch box-inspired rabbit hole.)

A Whole New World

The last few decades have brought a new lunch box revolution, of sorts. Plastic boxes begat insulated cloth sacks, and eventually, globalism brought tiffin containers from India and bento boxes from Japan. Even the old metal standby has seen a renaissance.

“I don’t think the heyday has passed,” says D.J. Jayasekara, owner and founder of lunchbox.com, a retailer in Pasadena, Calif. “I think it has evolved. The days of the ready-made, ‘you stick it in a lunch box and carry it to school’ are kinda done.”

The advent of backpacks threw the lunch box scene for a bit of a loop, he adds. Once kids started carrying book bags, that clunky traditional lunch box was hard to fit inside.

“But you can’t just throw a sandwich in a backpack,” Jayasekara says. “It still has to go into a container.”

That’s, in part, why smaller and softer containers have taken off — they fit into backpacks.

And don’t worry — whether it’s a plastic bento box or a cloth bag, lunch containers can still easily be plastered with popular culture.

“We sync with the movie industries so we can predict which characters are going to be popular for the coming months,” Jayasekara says. “You know, kids are kids.”